What Kind of Anmals Did the Serfs Feed

Medieval serfs (aka villeins) were unfree labourers who worked the land of a landowner (or tenant) in return for physical and legal protection and the right to work a separate piece of land for their own basic needs. Serfs made up 75% of the medieval population but were not slaves as only their labour could be bought, not their person.

Serfs might not have been slaves but they were subject to certain fees and restrictions of movement which varied according to local custom. The hub of the medieval rural community and reason for a serf's existence was the manor or castle – the estate owner's private residence and place of communal gatherings for purposes of administration and legal matters. The relationship of the peasantry to these manors and their lords is known as manorialism. Serfdom declined by the 14th century thanks to social and economic changes, particularly the wider use of coinage with which serfs could be paid, allowing some the possibility of eventually buying their own freedom.

Origins

The idea of people of different social levels living together on a single estate for mutual benefit goes back to Roman times when countryside villas produced foodstuffs on their surrounding land. As the Roman Empire declined and foreign raids and invasions became more common, the security of living together in a protected place had distinct advantages. The lord of an estate gave the right to live and work on his land to the peasantry in return for their labour service. Peasants were either free or unfree, with the latter category known as serfs or villeins. Serfdom evolved in part from the slavery system of the old Roman Empire. Without much property of their own, the serfs gave up their freedom of movement and their labour in exchange for the benefits of life on the estate of a landowner.

The most important function of serfs was to work on the demesne land of their lord for two or three days each week.

In addition to those born into serfdom, many free labourers unwittingly became serfs because their own small plot of land was barely sufficient for their needs. In such circumstances as a prolonged illness or a bad harvest, many freemen became serfs in order to survive, a downgrading frequently attested to in 1087's Domesday Book, a record of landowners and labourers in Norman England.

Follow us on Youtube!

Manors

Some country estates covered as little as a few hundred acres, which was just about enough land to meet the needs of those who lived on it. The smallest unit of land was called a manor. Manors could be owned by the monarch, aristocrats or the church, and the very rich could own several hundred manors, collectively known as an 'honour'. The majority of manors were like small villages as they created self-contained and independent communities. Besides a manor and/or castle, the estate had simple dwellings for the labourers and might also include a small river or stream running through it, a church, mill, barns and an area of woodlands. The land of the estate was divided into two main parts. The first part was the demesne (domain) which was reserved for the exclusive exploitation of the landowner. Typically, the demesne was 35-40% of the total land on the estate. The second part was the land the labourers lived and worked on for their own daily needs (mansus), typically around 12 acres (5 hectares) per family. The serfs on the estate farmed that land reserved for their use as well as the demesne.

July, Les Tres Riches Heures

Rights & Obligations

The most important task of serfs was to work on the demesne land of their lord for two or three days each week, and more during busy periods like harvest time. All of the food produced from that land went to the lord. It was sometimes possible for a serf to send a family member (providing they were physically able) to perform the labour on the demesne in their place. On the other days of the week, serfs could farm that land given to them for their own family's needs. Usually, serfs could not legally leave the estate on which they worked but the flip side was that they also had a right to live on it which gave them both physical protection and sustenance.

A serf inherited the status of their parents, although in the case of a mixed marriage (between free and unfree labourers) the child usually inherited the status of the father if legitimate and, if illegitimate, the status of the mother. In England and Normandy, the eldest son inherited the actual land worked on by their serf fathers, with daughters inheriting only if they had no brothers. Widows typically inherited around one-third of their late husbands' land. In contrast, in central and southern France, Germany and Scandinavia, inheritance was equal between sons and daughters of serfs.

Aside from payment to their lord of a regular percentage of the foodstuffs produced on their own land, the peasantry had to pay a tithe to the local parish church.

A landowner could sell one of his serfs but the right for sale was that of labour, not direct ownership of the person as in slavery. Theoretically, the personal property of a serf belonged to the landowner but this was unlikely to have been enforced or had any relevance in practical terms.

Aside from payment to their lord of a regular percentage of the foodstuffs produced on their own land, the peasantry had to pay a tithe to the local parish church, typically one-tenth of the peasant's harvest. The latter was used to maintain a priest, the church and provide a small welfare fund for the poor. In addition to those two heavy costs, a serf was obliged to pay fines and certain customary fees to their lord such as on the marriage of the lord's eldest daughter, or on the death of a serf in the form of an inheritance tax paid by the serf's heir. Fines were usually paid in kind for most of the medieval period, for example in the shape of the best animal the serf had. To protect the future generations of a landowner's serfs there were such customs as a fine for the daughter of a serf marrying a person from outside the estate.

Medieval Peasants Threshing

Serfs born into a large family very often did not receive any land of their own to work and so were obliged to continue to live in the home of their parents, marry another serf with land or live in the household of another peasant elsewhere giving their labour as rent. Other options included negotiating a new parcel of land from the lord, working for a local clergyman or trying their luck in a town or city where they might find unskilled employment working for a tradesman such as a miller or a blacksmith.

As customs varied from estate to estate and over time, there were some labourers who occupied a grey area of status between the free and unfree. One such category of serf was the ministerial serf in parts of France, Germany and the Low Countries. These serfs, still unfree in legal terms, had in practice more freedom of movement and could own their own property and land because they were the children of serfs who had served a lord as administrators or in some military capacity.

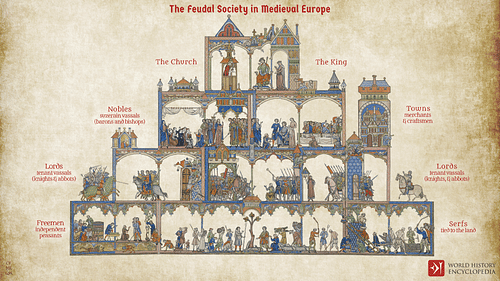

The Feudal Society in Medieval Europe

Daily Life

A description from the customs of the Richard East estate in England in 1298 records the following daily tasks expected of a serf:

He will plow and harrow at his own expense a fourth of an acre. And throughout the year he will work every second day, either carrying or mowing or reaping or carting, or doing some other work according as the lord or his bailiff commands him, except on Saturdays and major church holidays. And at harvest time he will find two men to reap for two days for the customary additional work at his own cost, that is two men on each day. And at the end of harvest time he will reap with one man for the whole day at his own cost.

(quoted in Singman, 85)

The lord was not completely heartless and did have one or two minimal obligations to observe himself:

All the aforesaid villeins at the end of moving will have sixpence for beer and a loaf of bread apiece. And he [the lord] must provide three bushels of wheat for the aforesaid bread. And each of the aforementioned mowers will have one small bundle of hay each evening, as much as he can mow with his scythe.

(ibid)

Men did the heavy agricultural work described above with women also doing lighter farm work and helping out at harvest time. Throughout the year women had their own extensive traditional duties such as milking, making butter and cheese, brewing ale (brewed from malted grains), baking bread, tending fruit trees, cooking in general, making wool and producing wool- and linen cloth, looking after poultry, household cleaning, and (probably) looking after any children.

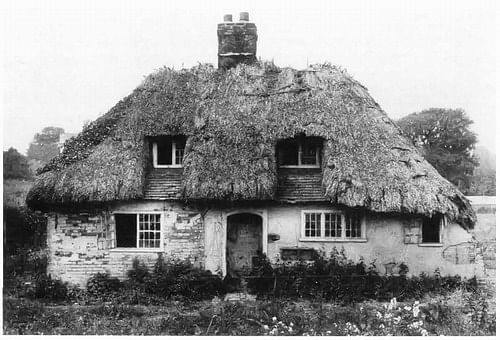

Medieval Peasant's Cottage

A tax assessment, compiled in 1304 for one Richard Bovechurch of Cuxham in England, gives an idea of what a serf of average wealth might own with the value of each item in shillings (s) and pence (d). There were 12 pence to the shilling.

- 1 horse - value 2s

- 1 cow - 4s

- 1 piglet - 6d

- 3 hens - 3d

- 1 bushel of beans - 3d

- 2 acres sown with grain - 4s

- 2 acres sown with vetch - 2s

- 1 cottage - 18 d

- 1 brass pot - 12d

- 1 pan - 3d

- 1 cart - 8d

Serfs typically lived in a modest one-story building made of cheap and easily acquired materials like mud and timber for the walls and thatch for the roof. There a small family unit dwelt; retired elders usually had their own cottage. More welcome than the in-laws, a dog and cat often proved useful, the former for herding and the latter for keeping down the number of rats in the granary. There was typically a hearth fire in the centre of the home which, besides a lot of smoke, provided warmth and light, as did candles. The windows of these simple dwellings had no glass but were closed at night using wooden shutters, and bedding was made of straw and woollen blankets. Farm animals were kept in a separate or attached building while a more prosperous serf family might also have a building for brewing beer and baking. A toilet was usually nothing grander than a hole over a cesspit, sometimes within a small shed for privacy but certainly not always. These domestic buildings were typically arranged around a courtyard to provide some protection from the wind.

Food & Leisure

Typical peasant food consisted of coarse bread made from wheat and rye or barley and rye; porridge made from barley or rye; and thick soup made from any of the following: cereals, peas, cabbage, leeks, spinach, onions, beans, parsley and garlic. The better-off peasants had milk, cheese and eggs, and meat was another rare luxury as farm animals were much more valuable alive, the most common meat being salted pork or bacon. Dried and salted fish and eels were available at a price. Fruit, usually cooked, included apples, pears and cherries, and wild berries and nuts were collected, too. The main drinks were weak ale or water with honey added. Few peasants would have had access to all the food just listed and most had diets lacking in fats, proteins, calcium and vitamins A, C and D.

January, Les Tres Riches Heures

A serf had leisure time on Sundays and on holidays when the most popular pastimes were drinking beer, singing, and group dancing to music from pipes, flutes and drums. There were games like dice, board games and sports such as hockey and medieval football where the goal was to move the ball to a predetermined destination and there were few, if any, rules. Serfs did get to live it up a little once a year when, by tradition, they were invited to the manor on Christmas day for a meal. Unfortunately, they had to bring along their own plates and firewood, and of course, all the food had been produced by themselves anyway, but they did get free beer and it was at least a chance to see how the other half lived and relieve the dreariness of a country winter.

Manor Courts

The manor had its own court run by the lord or his steward which was held a few times each year. In England, such a court, held in the great hall of a castle or manor, was known as a hallmote or halimote. Disputes between members of the manor estate such as the right to use particular areas of land like woodlands or peat lands (but not disputes between the lord and an individual peasant) were dealt with here, as well as the fines imposed on the estate workers and any criminal matters. Serious crimes such as murder, rape, and arson were judged in the courts of the Crown. The hallmote may have been biased toward the landowner but he was usually bound by the customs established by his predecessors and the ultimate decision of the court was actually in the hands of a jury, a panel of selected locals, usually fellow estate workers. This panel, typically consisting of 12 men, had evolved from the original jury of the early medieval period which referred to the men called by a defendant as character witnesses. There were also higher courts to appeal to and records show that the peasantry, acting collectively, could bring cases against a landowner.

Decline in Serfdom

The institution of serfdom was gradually weakened by several developments in the late Middle Ages. The sudden population declines caused by wars and plagues, particularly the Black Death (which peaked between 1347-1352) meant that labour was in short supply and thus expensive. Another trend was for free labourers to leave the countryside and seek their fortunes in the growing number of towns and cities. Runaway serfs could similarly try their luck and there was even a custom that by living for one year and a day in a town a serf earned his freedom. Without sufficient labour, many estates were abandoned. This situation gave serfs leverage to negotiate a better deal for themselves, even to receive a payment for their work. The greater use of coinage in medieval society helped make this possible and worthwhile. With saved-up money, Serfs could make a payment to their lord instead of labour in some cases or pay a fee to be absolved from some of the labour expected of them, or they could even buy their freedom.

Serfs increased their political power by acting collectively in village communities which began to hold their own courts and which acted as a counterweight to those of the landed gentry. Finally, there were sometimes serious revolts by the peasantry against their masters: the years 1227 in the northern Low Countries, 1230 on the lower Weser in northern Germany and 1315 in the Swiss Alps all witnessed violent peasant armies getting the better of those involving aristocratic knights. A major but unsuccessful rebellion, the Peasants' Revolt, which called for the end of serfdom occurred in England in 1381. Across Europe, all of these factors conspired to weaken the traditional setup of unfree labourers being tied to the land and working for the rich so that by the end of the 14th century CE, more agricultural labour was done by paid workers than unpaid serfs.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Serf/

0 Response to "What Kind of Anmals Did the Serfs Feed"

Enregistrer un commentaire